The Oatmeal, Nikola Tesla, and Geek Chic Rhetoric

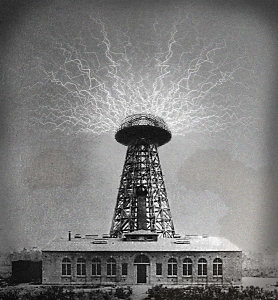

In the last two weeks Matthew Inman’s crowd-funding campaign “Let’s Build a Goddamn Tesla Museum” raised over $1,148,0000 to preserve Wardenclyffe (1901-1917), the 200-acre site seventy miles east of New York City where the scientist and inventor Nikola Tesla built a tower to wirelessly transmit electric power across the Atlantic. Tesla’s plans for a “Worldwide Wireless System” did not succeed: his tower was torn down in 1917, Tesla slipped into obscurity, and one of the most important inventors of the electrical age died alone and broke in a New York hotel room in 1943. Now Inman, creator of comedic website The Oatmeal, has captured worldwide attention with his attempt to restore the massive laboratory at Wardenclyffe and to give overdue recognition to this “cult hero to geek people.”

Reactions to Inman’s viral fundraiser have been mixed: media gurus seem awestruck by Inman’s successful crowd-sourcing and how he convinced Paypal founder Elon Musk to contribute. Others seem bothered by the comedian’s “colorful language,” his spread of “Tesla idolatry,” and the possibility that the campaign’s foundation in “geek mythology” and “fairy-stories” may deter from the proposed Tesla Science Center’s presentation of “science as a process that concerns us all, not just science geeks.”

The popular views of Inman as a savvy social media-lite and Tesla as an eccentric, underappreciated electrical genius overlook the fact that they are talented writers who use what we might call “geek chic rhetoric”: they bring marginalized, complex, geeky ideas (and persons) into the mainstream by embracing popular modes of persuasion and selectively avoiding commercial marketing and technical jargon.

Sophisticated “Douchebaggery”; or, How I Would Teach The Oatmeal

(CC) Randy Stewart, blog.stewtopia.com. Feel free to use this picture. Please credit as shown. If you are a person that I have taken a photo of, it’s yours (but I’d still be curious as to where it is). (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

As a college writing instructor, if I were to bring my students’ attention to Inman’s illustrated blog posts—“Why Tesla Was the Greatest Geek Who Ever Lived” and “Let’s Build a Goddamn Tesla Museum”—I would begin by stating the obvious: phrases like “the only thing Edison pioneered is douchebaggery” or “I hope a Nazi torpedo hit [Edison’s] grandchildren right in the mouth” are unacceptable in professional settings. Then, I would ask the class to consider the more sophisticated rhetorical choices the author makes in these two relatively short, illustrated essays and why those choices may have inspired over 20,000 people from across the planet to give cash (an exponentially stronger investment than a “like”) in honor of a relatively obscure historical figure. Here are a few answers:

1. Ad hominem

At times Inman seems more interested in denigrating Edison than celebrating Tesla, but focusing on the rivalry between Edison and Tesla represents ad hominem: strengthening one position by attacking another. Hate Edison, like Tesla. It is easy to dislike Edison. Tesla claimed his former boss cheated him out of a $50,000 bonus in the 1880s while Tesla was a poor Serbian immigrant struggling to make ends meet in New York. Years after Edison and Direct Current lost the “War of Currents,” Edison used alternating current to electrocute animals, including an elephant (Here is video evidence). Inman may be bias, but, as far as historical accuracy, he rises above the hilarious and sloppy “Drunk History: Tesla” without getting totally wrapped up in the conspiracy theories (free worldwide wireless energy and confiscation of Tesla’s “death ray,”) that captivate most Tesla geeks and perpetually pull at the foundations of more sober Tesla biographies. By making Edison out to be the archetypal American CEO (“a non-geek operating in a geek space”), Inman shows solidarity with the existing Tesla fan base and also appeals to less geeky readers who might be leery of the Edison-inspired corporations currently embroiled in controversy: Consolidated Edison, Southern California Edison, or General Electric.

2. Dialectic:

Inman often uses seemingly simple dialectic, asking basic “Ever heard of X?” or “Did you know Y?” questions and then offering factual answers alongside additive images.

3) Pathos

At his best, Inman mixes intelligence and belligerence to create pathos not unlike that displayed by Robert Crum’s comics or Charles Bukowski’s poetry. To counter the dirty language, his work has a clean, DIY feel that is not separated by panels or page breaks. His handling of font size, capitals, and shorthand also adds pitch to his web-based essays: geeky “facts” often appear in normal size font; capitals are often used to make a point. Rarely does the mix of strange facts and badly drawn bears appear so sexy.

4) Kairos

The Oatmeal became famous for addressing the cute—bears and kittens—and the quirky—Sriracha sauce and apostrophes—with humor and intelligence. Yet “Build a Tesla Museum” is his most timely piece and a great example of kairos: the art of making an appeal at the propitious moment. Inman’s first piece about Tesla was a huge success; drawing millions of retweets and “likes” from readers across the world. Months later, the author learned that Tesla’s Wardenclyffe laboratory was for sale and that if the Tesla Science Center could raise 850k, the state of New York would match it. The threat of the abandoned laboratory falling into the wrong hands added urgency, donating directly to an existing foundation—the Tesla Science Center—via IndieGogo made donating added safety, and state’s offer of a matching 850k grant lent legitimacy. Inman made his move—and the Internet responded.

Which great inventor of the electrical age was also a great writer? Nikola Tesla

The campaign should bring overdue recognition to Tesla’s electrical inventions and Tesla’s electric rhetoric. Following the overarching “Tesla is better than (or at least equal to) Edison” equation, we look to Charles Bazerman’s The Language of Edison’s Light (2002) which examines “the rhetoric used to create meaning and value for the emergent [light bulb] technology.” What type of rhetoric did Tesla use to introduce his ideas about electricity?

Tesla’s lectures and essays from the 1890s illuminate contemporaneous thoughts about electricity, technology, and nature. Here we find the cosmic hopes and widespread fears that underlay the discovery of new energies in increasingly fragile and wondrous environments; we find wild visions of harnessing free energy from the atmosphere and communicating with Mars; we find exact, thought-by-thought analysis of the most banal perceptions (a pigeon on a window sill) and sophisticated mental processes (designing the alternating current motor). Tesla’s lofty, Sagan-esque style sometimes gets the better of him and his ideas float away to seem overly poetic or simply far-fetched; yet, at its best, Tesla offers Emerson-like turns of phrase that portray mankind and electricity embarking on an exchange of exquisite, sublime force.

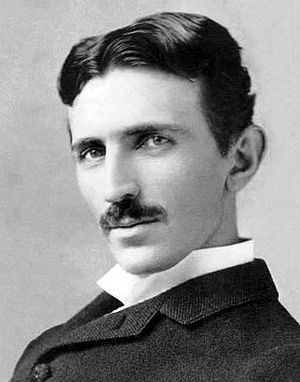

Consider Tesla’s 1891 lecture at Columbia College—“Experiments with Alternate Currentsof Very High Frequency, and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination.” This was one of the first public discussions of the scientific principles underlying the electrical illumination of businesses and homes and was, in many ways, Tesla’s New York debut. The tall, slender, dark-haired Serbian with sparkling eyes opened by stating that the collective understanding of imperceptible phenomena like electricity was advancing because “far beyond the limit of perception of our senses the spirit still can guide us…Instinctively we feel that the understanding is dawning on us.” As he looked towards the crowd, he said that humanity was being pulled towards an “immeasurable, all-pervading energy”: electricity was like “a soul” that “animate[d] the inert universe.” Despite the widespread vertigo suggested in his conclusion—“We are whirling through endless space with an inconceivable speed, all around us everything is spinning, everything is moving, everywhere is energy”—the audience was not thrown off.

Days later the New York Times praised Tesla for bringing to light “the most occult branches of theoretical electricity” with “layman’s descriptions.” Harper’s Weekly congratulated him for describing his theories in “pure, nervous English” and delivering a three-hour “rhetorical performance.” Indeed, for a non-native English speaker struggling to distinguish the complex and sometimes competing interests of scientific research, practical invention, and American finance, the lecture was a startling success.

Shortly thereafter, Tesla became one of the most respected thinkers in the world. The fame and success fed his ambition: he was not content just to invent, he wanted to initiate a worldwide revolution. He worked endlessly and barely slept: he became alternatively bold and exhausted. In 1897, on a cold night in Buffalo, approximately four hundred scientists, engineers, and politicians gathered to celebrate Tesla and transmission of electricity from nation’s first hydroelectric power plant at Niagara Falls. Tesla’s name was listed thirteen times on the bronze patent plaque attached to the Niagara Falls Power House and the New York Times claimed: “To Tesla belongs the undisputed honor of being the man whose work made this Niagara enterprise possible.”

The audience greeted Tesla with thunderous applause. A witness reported, “The introduction of Nikola Tesla, the greatest electrician on earth, produced a monstrous ovation. The guests sprang to their feet and wildly waved napkins and cheered for the famous scientist. It was three or four minutes before quiet prevailed.” Tesla seemed overwhelmed. He began his speech “On Electricity,” by admitting that he felt so “full of the subject” that he could not “dwell in adequate terms of this fascinating science.”[i] He continued, in an embarrassed, self-deprecating tone:

…as I shall attempt expression, the fugitive conceptions will vanish, and I shall experience certain well known sensations of abandonment, chill and silence. I can see already your disappointed countenances and can read in them the painful regret of the mistake in your choice.

Tesla was humbled by the achievement at Niagara and the invitation to speak, but the notion that he lacked “the fire of eloquence” was more as of a self-deprecating rhetorical gesture. For the remainder of the talk, Tesla did not just speak “on” his subject, but with it. Electricity was not just a potent factor for intellectual discourse or even a tool of progress; it was the characterizing feature of the mind and the gauge for progress. His scope expanded, and he recited the wonders of electrical science:

Electrical science has revealed to us the true nature of light, has provided us with innumerable appliances and instruments of precision…added to the exactness of our knowledge…attracted the attention and enlisted the energies of the artist; for where is there a field in which his God-given powers would be of a greater benefit to his fellow-men than this unexplored, almost virgin, region, where, like in a silent forest, a thousand voices respond to every call?

Such statements resemble Ralph Waldo Emerson’s claim that the poet is “a conductor of the whole river of electricity”: If Emerson’s poet was an electric conductor; Tesla’s electrical engineer was a poet.

Tesla was also aware of Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis—offered at the Columbian Exposition of 1893 which used Tesla patents for power. Turner famously argued that the unsettled West had been a cultural and political lynchpin of the nineteenth century; For Tesla, the “unexplored, almost virgin, region” of electricity would be a driving force for the scientist, the philosopher, and the artist of the twentieth.

Tesla saw electricity as a panacea: it would cure health problems, eradicate poverty, end military conflicts, and make everyday life more comfortable. Lawmakers, economists, and philanthropists, according to Tesla, could only provide “temporary” relief for struggling masses: “If we want to reduce poverty and misery, if we want to give to every deserving individual what is needed for a safe existence of an intelligent being, we want to provide more machinery, more power.”

By the end of his speech, Tesla told the audience that had gathered to celebrate the nation’s first long-range transmission line that he was prepared to transmit significant amounts of electric power “without the employment of any connecting wire.” Months before Marconi shocked the world by sending a simple series of Morse code signals across the English Channel (over distances of six to sixteen kilometers), Tesla was already thinking of sending high voltage power (not just pulses) across the Atlantic.

Just as the Internet has become the exceptional, all-pervasive force in the modern mind, the intellectual and social developments that defined the late nineteenth-century were charged by the science of electricity. Technological advances like light bulbs, induction motors, and electric trains and subways were changing the way people worked, communicated, and thought about the world. Widespread electric power promised to accelerate those changes and transform almost every aspect of existence. Very few Americans had electricity or even had the language or metaphors with which to understand these recent developments or see how “electricity” would shape the future. Electricity was still relegated to the “geeks,” but Tesla’s written work opened the conversation to a wider audience and for those inventions, he also deserves recognition.

[i] I quote from the copy of Tesla’s speech “On Electricity” printed in Nikola Tesla: Lectures, Patents, Articles (Belgrade, Yugoslavia: Nikola Tesla Museum, 1956), pp. 101–8. A transcript of the speech appeared in the Electrical Review, January 27, 1897.